|

PFD |

|

|

PFD |

|

|

David Grindley (Stage Director) |

|

Agent NS: Nicki Stoddart |

|

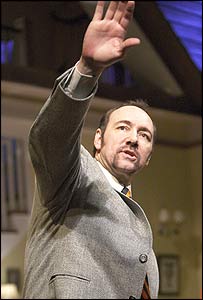

In January 2005 David Grindley directed Kevin Spacey in NATIONAL ANTHEMS by Dennis MacIntyre at the Old Vic Theatre, London. It is Spacey's acting debut as Artistic Director of Old Vic Theatre Productions. NATIONAL ANTHEMS opened on 8 February 2005. |

|

Director |

|

|

2005 |

NATIONAL ANTHEMS by Dennis MacIntyre Starring Kevin Spacey |

Old Vic Theatre, West End |

|

2004 |

JOURNEY'S END by R C Sheriff |

Comedy Theatre, West End, transferred May 2004 to Playhouse Theatre, West End |

|

2003 |

EXCUSES! by Joel Joan &

Jordi Sanchez |

Actors Touring Theatre, National tour and Soho Theatre, London |

|

2002/2003 |

ABIGAIL'S PARTY by Mike

Leigh |

Hampstead

Theatre (with Theatre Royal Bath Productions) transferred to New

Ambassadors, West End December 2002, moved to Whitehall Theatre, West End

spring 2003, followed by 2 National Tours |

|

2002 |

SINGLE SPIES by Alan Bennett |

National Tour - Theatre Royal Bath Productions |

|

2001 |

MENTAL |

Edinburgh Suite

Assembly Rooms |

|

2001 |

HAVING A BALL |

National Tour (Richard Temple Productions) |

|

2000 |

WAIT UNTIL DARK |

Royal Theatre Northampton |

|

2000 |

THE ERPINGHAM CAMP |

Liverpool Everyman & Edinburgh Festival 2000 |

|

2000 |

ALARMS & EXCURSIONS |

Argentina |

|

2000 |

THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE |

Royal Theatre Northampton |

|

1999 |

RICHARD III |

Mercury Theatre Colchester |

|

1999 |

THE REAL INSPECTOR HOUND & BLACK COMEDY |

National Tour |

|

1999 |

LOOT |

National Tour (Paul Farrah Productions) |

|

1998 |

LOOT |

Vaudeville Theatre, West End |

|

1998 |

LOOT and SEXUAL PERVERSITY IN CHICAGO |

Minerva Studio Co-Ordinator and Staff Director for Chichester Festival Theatre |

|

1998 |

BLACK COMEDY and THE REAL

INSPECTOR HOUND |

Comedy Theatre, West End |

|

1997 - 1998 |

THE MAGISTRATE |

Savoy Theatre, West End (Duncan Weldon) |

|

1997 |

Chichester Festival

Theatre: |

|

|

1997 |

BEING THERE WITH PETER

SELLERS |

Stoneranger, National Tour |

|

1997 |

BEING THERE WITH PETER SELLERS |

The Pleasance, London |

|

1997 |

THE HUMAN VOICE |

|

|

1996 |

Chichester Festival

Theatre: |

|

|

1996 |

THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN |

Canal Cafe

Theatre, London |

|

1995-1996 |

PRIDE AND PREJUDICE |

Good Company Theatre Productions, tour |

|

1995 |

TOWARDS THE MILLENNIUM -

THE FORUM FOR EUROPEAN THEATRE DIRECTORS |

|

|

1995 |

THE SMALLEST CINEMA IN THE

WORLD |

Edinburgh Festival |

|

1995 |

CAUGHT IN THE NET |

Arts Theatre, West End |

|

1994 |

BABEL |

Pleasance Theatre, London |

|

1994 |

Programmer for Pleasance Theatre Festival |

|

|

1993 |

OTHELLO |

Edinburgh

Festival. |

|

1993 |

OUR BOYS |

Cockpit Theatre |

http://www.britishtheatreguide.info/otherresources/interviews/DavidGrindley.htm

http://www.britishtheatreguide.info/otherresources/interviews/DavidGrindley.htm

Interviews

David Grindley

Philip Fisher interviews the director of Abigail's Party, whom Mike Leigh described as "one of the most important young directors that we have."

David Grindley is one of life's enthusiasts. He positively gushes his views, always constructive, on a variety of subjects. This probably makes his life as a freelance theatre director that much more palatable. It is not easy to carry out one project without knowing what, if anything, one will be doing when it finishes. This has become an even greater consideration now that he is a very proud father of a six-month-old son.

As a consequence, the incredible success of his revival of Mike Leigh's Abigail's Party is that much sweeter. It completed a sell-out 16-week run at the Hampstead Theatre, where the original production had been put on 25 years before. Now it has moved to the New Ambassadors - one of the very few suitably intimate West End theatres - and was nominated for Best Revival at the Olivier Awards.

Grindley first fell in love with theatre when he was ten while watching his mother acting and directing in amateur dramatics in Sussex. He was soon using Lego men and blow-up sets from the back of Samuel French texts to direct his own mini-productions.

Although he auditioned for drama school, he was always keener to direct than act. "I enjoyed acting but directing and interpreting texts, not to mention the opportunity to be involved in and responsible for the whole of a show, was what I wanted to do."

Grindley's first break was with his own production of Othello on the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 1993. This was presented in true Fringe spirit, with a female Othello and a male Desdemona. The show was a huge hit and was nominated for an Independent Award prior to a transfer to the Battersea Arts Centre.

In 1996 Grindley was invited to become assistant director at Chichester. He helped 15 different directors and the highlight was an Uncle Vanya starring Derek Jacobi, Imogen Stubbs, Trevor Eve and Frances Barber. This subsequently transferred to the West End and was televised. During his time at Chichester, Grindley was lucky enough to work with such strong influences on his career as Michael Rudman, Bill Bryden and Robin Lefevre.

In 1998 he became programmer at the Minerva Theatre in Chichester. He operated in the spirit of Sam Mendes, allowing young actors from the main house to play leading parts in the smaller theatre. The big success of this season was his production of Loot, which subsequently transferred to the Vaudeville Theatre for a three-month run.

So far, Grindley has tended to direct comedies. He thinks that this is because he is regarded as a safe pair of hands with comic material. He would love to do more Shakespeare and especially Chekhov. He uses comedy to get absolutely the right balance between light and shade: "I'd love to do Vanya again."

Perhaps the strangest assignment of his peripatetic career to date has been producing the quintessentially English Michael Frayn's Alarms and Excursions in Spanish with a translator, achieving remarkable success in Buenos Aires.

Grindley is a very hands-on kind of a director who will visit his productions on a constant basis. It is important to him that his actors feel comfortable and he is a collaborative director who wants to involve his actors and design team in major decisions.

He and Abigail's Party's leading lady, Elizabeth Berrington, both emphasise that it is a real team effort between the five actors and the young creative crew. It is clear that this is a show they all love and that has struck a chord with audiences.

Grindley has been a fan of Leigh's work, Abigail's Party in particular, for many years. "Mike Leigh is a great man. He has managed to keep his sense of purpose and values together with a sense of humour throughout his career.

"He is a superb advocate for young people and has fully supported this creative team. He has never doubted the decisions that have been taken and has always been a stalwart - right behind us."

Leigh encouraged Grindley to direct the revival and has also seen the production countless times. He has only praise for Grindley: "He is a very talented all-round director with a good sense of theatre and a great way with actors. He has done an amazingly good job. It is a production both orthodox and fresh - original, sparky and real."

Grindley emphasises: "The production at Hampstead was a risk, since many members of the audience had fond memories of the original. In fact, the audience response there was incredible." He has no doubt that live performances will always prove a richer experience than the videotaped version. Even those notorious Hampstead Saturday afternoon audiences have bought in and responded marvellously. There are not many theatre directors who can say that.

One good thing is that the cult popularity of Abigail's Party has allowed Grindley complete casting freedom. He is well aware that in order to achieve commercial success, it has become de rigueur to find major Hollywood names or British television stars who can fill a theatre. This can be the case irrespective of the nature of the play or, on occasion, the performances.

Although he is not averse to working with famous people, this freedom means his options are never limited. In fact, many actors who auditioned were scared by the play's previous success, believing that the original production would overshadow any work they did.

In the spirit of teamwork that he so positively espouses, this young director, who was only seven years old when the original production found an audience of 16 million on prime-time Saturday night television, emphasises that "these actors have marched away into the West End by creating a fantastic show". He is delighted that even after over 150 performances, the production remains fresh.

He also pays great tribute to the dedication of his actors. "The accents are in a very narrow register and potentially could wear their voices down." Ironically, as he says this, the rather attractive contralto of Berrington can be heard as she exercises her vocal cords prior to going onstage. He says of her Beverly: "She built it from the ground up. She has really made the role her own and has paid no heed to Alison Steadman's original." This is in part due to the fact that, remarkably, she has never seen the TV version.

He has been lucky in his casting in that, as he says: "It is hard to find contemporary actors who have a real comic sensibility. Nowadays, all the best comic jobs go to stand-up comedians and there is a dearth of comic actors." He has no doubt that the current cast has this sensibility but would not relish recasting the show if that ever became necessary.

His vision for the play is strong. "This was a very charged time and Abigail's Party was a groundbreaking play that caught the mood of the time, which was that of a battle between the aspirational Beverly types and the teenage punks with their nihilistic attitudes." It is this nihilism that Grindley catches perfectly with his inspired use of The Sex Pistols' God Save the Queen in the final scene.

Grindley does not necessarily see his career ending in theatre, though he loves its sociability, the team atmosphere and the special magic. He may well look further afield, as he says: "I would like to do a film, maybe even get to Hollywood like Sam Mendes or Stephen Daldry."

A trip to America might well do him good, as he believes that at the moment the best new writing is American. In particular, he selects Richard Greenberg who has already had two recent successes at the Donmar with Three Days of Rain and Take Me Out.

Whichever course Grindley's career takes, he is the kind of man who will have fun and put his all into whatever he is doing. If that is not a recipe for success, there is something wrong with the world.

Mike Leigh, has no doubts about that success. He sums up Grindley's enthusiasm in the most positive way. "David Grindley is one of the most important young directors that we have."

This interview first appeared in The Stage

http://www.albemarle-london.com/ShowInfo.php?Show_No=7597

Journey's End

Play by R C Sherriff. Directed by David Grindley.

First performed in 1929, RC Sheriff's great anti-war classic Journey's End is set in the British trenches at St Quentin, and is based on the author's own experiences of the Front.

Lieutenant Raleigh has joined the army straight from school and finds himself posted to the Company of Captain Stanhope, barely three years Raleigh's senior and his idol from school. But Stanhope, promoted beyond his experience and years, has changed, and now faces the inevitabilities of the front line.

Journey's End is filled with humour in the face of certain tragedy and is as much the story of its many characters as it is an observation on war.

David Grindley West End credits include National Anthems (Old Vic 2005) and the revivals of Mike Leigh's Abigail's Party (New Ambassadors Theatre 2003 then Whitehall Theatre 2003) and Joe Orton's Loot (Vaudeville Theatre 1998).

Following a successful thirteen month season in London's West End between January 2004 to February 2005, this production returns to London 'by popular demand'!

Extracts from the reviews

From the original cast at The Comedy Theatre 2004:

"Journey's End is the play about the First World War. Staged in 1929 it pulled no punches in showing the public what utter hell life in the trenches was. This tin hat period piece shouldn't by rights work today... Yet somehow the piece grips you by the scruff of the neck; the three suspenseful acts building up to the final attack is terrific entertainment... David Grindley directs the production superbly... Wonderful stuff." The Express

"We've had Birdsong, the Pat Barker trilogy and the rediscovery of Miles Malleson's anti-war plays. Yet, for all our renewed awareness of the first world war, RC Sherriff's 1928 play still works powerfully on our emotions, especially in a revival as good as David Grindley's... This is not an overtly anti-war play; but everything about Grindley's production, from the peacetime dreams of Paul Bradley's working-class lieutenant to the final ghostly image of the entire company standing before a marble cenotaph, leaves one feeling overwhelmed by the wasteful horror of war." The Guardian

"If you've never seen R.C. Sherriff's Journey's End, don't miss this chance... It's never ceased to earn admiration for its gripping portrayal of four days among the British officers of one battalion on the front in 1918... From the opening dropcurtain of the royal family in 1914-18, to the closing list of those who died, this production is utterly fresh; the characters are deeply touching. David Grindley directs: even the pauses are wonderful... I expected to find Journey's End old hat. Instead it is as compelling, as moving, as anything in London theatre today..." The Financial Times

"...David Grindley's superbly acted production, with a marvellously detailed and atmospheric dug-out design by Jonathan Fensom and a striking closing tableau that raises the hairs on the back of the neck, never sounds a single false note... Geoffrey Streatfeild announces himself as a star in the making as Stanhope... David Haig is superb... And there is fine work from Christian Coulson... from Paul Bradley...and Ben Meyjes as the panic-struck malingerer..." The Daily Telegraph

National Anthems

Play by Dennis MacIntyre. Directed by David Grindley.

Birmingham, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit, in the late 1980s. Arthur and Leslie Reed, newcomers to the area, are clearing up after a party. Suddenly one of their neighbours, Ben Cook, arrives on the doorstep unannounced to introduce himself. But what seems at first like a friendly visit gradually turns into something very different. As the night wears on the tensions within the Reeds' marriage slowly come to the surface, while Ben's failed ambitions and damaged past push his bitterness and suppressed violence to the limit. The party games increase in intensity and the emotional barriers come tumbling down, culminating in a devastating clash of wills, values and bodies.

Played in real time, Dennis McIntyre's raw and shocking play is at once a searing critique of suburban values and a hard-hitting parable about American materialism. Shot through with wit, pain and anger, it paints a powerful and honest portrait of male competitiveness, status anxiety, and the fragile nature of a marriage built on the worship of consumer goods rather than love.

Cast stars Kevin Spacey as 'Ben Cook', Mary Stuart Masterson as 'Leslie Reed' and Steven Webber as 'Arthur Reed'.

|

Superseats A limited number of superseats are available for performances of National Anthems priced at £125.90 each. The price includes a glass of champagne and a free programme. |

Kevin Spacey last played on stage at The Old Vic Theatre in Howard Davies' critically acclaimed 1998 revival of Eugene O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh.

This production marks the West End debuts for both Mary Stuart Masterson and Steven Webber who have both recently been seen in award-winning shows on Broadway - Mary Stuart Masterson in Nine and Steven Webber in The Producers.

Dennis McIntyre was born in Detroit, and died in 1989. His play Modigliani, a ribald comedy about artists struggling to survive in 1916 Paris, focussed on three days in the troubled personal and professional life of the self-destructive Italian artist. Rewritten and produced on Broadway in 1980, it was, staged in London in 1987. Split Second, an explosive encounter between a black Manhattan police officer and a white car thief, was produced in New York in 1984, had its European premiere in Edinburgh, and was later presented in London, as well as several American cities. Established Price, a tale of white-collar angst in the age of corporate takeovers, was first staged in 1967.

National Anthems was first produced at the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut and at the GeVa Theater in Rochester, New York. In 1988 it was staged at the Long Wharf Theater in New Haven, Connecticut, directed by Arvin Brown and starring Kevin Spacey, Tom Berenger and Mary McDonnell.

Extracts from the reviews

"...A little-known playwright called Dennis McIntyre based this claustrophobic, laughter-laced satire in late 1980s suburban Detroit... Mr Spacey is on fine form. He has the waxy face, clunky shoulders, the 'let me tell ya something!' relentlessness that can make suburban bores such social terrorists. In places teh comedy of refined manners makes this an American Abigail's Party... National Anthems is fluent, funny, an easy watch with several good lines. The set opulent, the acting more perfect then the casting..." The Daily Mail

"...Spacey plays Ben Cook... This is a role he played in the 1988 American premiere, and he is terrific, up to a point. The combination of neurosis and comedy is brilliant, often disarming. But why is he heating up this 17-year-old meal?... You can sense Spacey the canny operator, steering us along; and it is this canniness that stops us getting inside Ben's nervous system. A wicked performance; not a dangerous one... David Grindley directs: good variation of tone throughout... Spacey's co-actors, Mary Stuart Masterson and Steven Weber, are excellent." The Financial Times

"...It is sparkily acted, with Spacey in particular delivering a splashy star turn. But the play feels shallow, contrived and dated... The dramatist's editorialising portrayal of racism and class conflict often seems more like a political pamphlet than a play. David Grindley... gets the most out of the jokes but can't conceal the glib nature of the play, while his staging of the violence proves far too tame. Spacey is initially charismatic and unsettling as the troubled fireman but is reduced to an embarrassing solo turn of blubbing sentimentality by the end..." The Daily Telegraph

"...While Spacey is mesmerising to watch, McIntyre's play offers a glibly mechanical metaphor for American life... But, even if McIntyre's play fails to deliver, it creates a fine part for Spacey... Spacey doesn't just occupy the stage, he seizes it by right. And, even in the stagey football contest, he is devastatingly funny... In McIntyre's play he gives a dazzling performance but he looks like a great boxer in an exhibition bout." The Guardian

Abigail's Party

New Ambassadors

Theatre: Previewed 3 Dec, Opened 4 Dec 2002, Closed 5 April 2003 transferred to

Whitehall Theatre: Opened 9 April 2003, Closed 12

July 2003

Play by Mike Leigh, directed by David Grindley designs by Jonathan Fensom, lighting by Jason Taylor and sound by Gregory Clarke.

Twenty-five years ago Hampstead Theatre in North London gave Mike Leigh a locked rehearsal room, five actors and six weeks to develop a play.

The result? Abigail's Party, which became not just a modern classic but a national treasure... now, twenty-five years later, David Grindley's critically acclaimed revival staged this year at the Hampstead Theatre transfers to the West End's New Ambassadors Theatre.

It's the year of the Queen's Silver Jubilee: the Sex Pistols are gearing up to blow Donna Summer and Demis Roussos out of the charts forever, while the suburbs are awash with the new money and social aspiration which would sweep the Conservatives into power for the next twenty years...

This production has received 1 nomination at the 2003 Olivier Awards for 'Best Revival'.

Cast (as of December 2002): Elizabeth Berrington as 'Beverly' (played by Alison Steadman in the original 25 years ago), Rosie Cavaliero, Wendy Nottingham, Steffan Rhodri and Jeremy Swift.

Cast (as of April 2003): Elizabeth Berrington as 'Beverly', Philip Bird, Amelda Brown, Elizabeth Chadwick and Jake Wood.

Extracts from the reviews:

From the New Ambassadors Theatre run:

"...The great thing about this production is that Elizabeth Berrington, sporting a hideous lime-green dress, overcomes the memory of Alison Steadman in the role of Beverly Moss; she is fabulously unpleasant... Director David Grindley brilliantly brings out the sheer blackness of the comedy as the guests' gin starts to kick in. The cast is spot on... The evening holds up beautifully a quarter of a century on. If you loved it first time round, you won't be disappointed." The Express

"...As Beverly, Elizabeth Berrington is good but obvious. She reveals too much too soon. She is like a diva whose first appearance on stage sees her hitting all the top notes. There is nowhere else for her to go. It is an entertainingly comic performance... Looking rather tame against the viciousness of some modern satire, Abigail's Party survives most successfully as a period piece, a social document that lays bare the attitudes and aspirations of the lower middle classes..." The Guardian

"...Elizabeth Berrington more than lives up to Steadman's memory in this 25th anniversary production of Mike Leigh's cruel satire... David Grindley's production allows cracks of pathos to open up between the laughs. But his frisky cast can't quite dispel the misanthropic clouds that still hang over Leigh's play." The Daily Mail

"...Beverly, first immortalised by Alison Steadman, is superbly played here by Elizabeth Berrington, in a tour de force of vulgar, bogus bonhomie that also suggests a woman who is half aware that her soul is dead. Jeremy Swift's seething fury as her hapless husband, Rosie Cavaliero's mindless prattle as Ange, Steffan Rhodrie's cruelty as Tony and Wendy Nottingham's anxious misery as Susan are all impressively caught in David Grindley's sharp, heartless production, designed with an eagle eye for 1970s naffness by Jonathan Fensom. It's shamefully entertaining stuff - the modern equivalent of visiting Bedlam to laugh at the lunatics." The Daily Telegraph

Loot

Comedy by Joe Orton. Directed by David Grindley.

This outrageous comedy sees two likely lads, Hal and Dennis, make off with the swag from a bank robbery. In hot pursuit by Inspector Truscott, who swears he's from the Water Board, and Fay, a Florence Nightingale with the bedside manner of Boudicea, our intrepid heroes are forced to bury the money in the last place anyone would look.... Meanwhile the recently widowed Mr McLeavy is trying to mourn for his late wife - but his son Hal's exploits turn the funeral into a right carry-on.....

VAUDEVILLE Theatre. Previewed 10 August, Opened 12 August 1998, Closed 7 November 1998

Extracts from the reviews:

|

"Joe Orton's exhilarating mid-Sixties high comedy of low

taste has lost none of its rapacity to disturb and surprise. A corpse is

laid out for burial in her WVS uniform. The son and his friend, an

undertaker's assistant, have robbed a bank. The private nurse has her eye

on the widower. And the corpse's eye is rolling about the floor. The money

is stashed in the coffin, the corpse in the cupboard. Enter Truscott of

the Yard, passing himself off as a water board official. As the plot

unravels, the widower McLeavy is involved in a catastrophe with the

cortege and the nurse, Fay, unmasked as a genocidal fortune hunter. Loot

is a glittering, beautifully written force of bad manners and furious

slights against the superstition of death and organised religion. The cast

in David Grindley's production is relatively unknown, but they perform

with gleeful precision and some expertise. Fred Ridgeway is an honest

supporting actor who plays Truscott as a jumped-up official with an

Estuary whine and a fetish for his own dignity. Tracy-Ann Oberman is a

sharp and knowing Fay, and Gary Whitaker and Alexia Conran deeply

disturbing partners in crime and cruel punishment. A most bracing, welcome

summer filler in the West End list." Michael Coveney, The Daily Mail "Squeezing deadly fun from a corpse - Did anyone apart from Joe Orton squeeze so much theatrical fun from an embalmed corpse dressed in a WVS uniform and then undressed? Was the gruesome majesty of death, with one glass eye and some defunct dentures looming large, ever so amusingly mocked? Surely not. Corpses, before Orton got to them, were rarely any laughing matter. Three decades after the 1966 premiere this madcap farce, with its cynical mockery of corrupt policemen, Catholicism and loveless family relations, still hits home with the sting of sharp comic wit. It puts bad taste to good use. David Grindley's production, which happily comes up to town from Chichester Festival's studio theatre, is slightly handicapped by its penny-pinching, amateur look. Stuart Wood's set gets down to bare essentials with hanging crucifix, coffin and portable lavatory and never rises above them. Fortunately it's no real setback. What matters most in Orton is the tone and style of performance. You need cool actors using just a touch of camp - deadpan and deadly serious - who never emphasise the extravagances and immoralities with which Orton equips his characters. When that style is achieved Loot spirals into black comedy, to an anarchic world where wickedness and hypocrisy put all goodness to flight. Last night, particularly thanks to a dazzling performance of comic star potential by Fred Ridgeway as Detective Inspector Truscott, Orton casts his old black magic spell again. Ridgeway's Detective, in a spooky grey hat which he refuses to move, has the look of a man up to no bad. He reeks of non-descript ordinariness in his pose as a water board man who wanders into a house of grief where Mrs McLeavy's remains are poised for immortality. Hardly has he set a probing foot inside than Truscott is caught in a conspiracy involving that coffin, the corpse and thousands of bank notes. Bad taste takes a first bow and never really leaves the stage. A mummy in both senses of the word is involved, not to mention the undertaker's assistant Dennis, his slightly sexual sidekick - McLeavy's son, Hal - and Tracy-Ann Oberman's young Irish Nurse Fay, whose special hobby is collecting and marrying men to murder for money. Orton's comedy springs from the way in which his immoral characters put on shows of virtue, conformity and pomposity or are shamelessly wicked. Never before has the play seemed so close to the theatre of the absurd or soared to such Lewis Carroll-like heights of nonsense. As the flagrant Truscott threatens and hectors, Ridgeway's speech begins to speed and hurtle. A gleeful fanaticism possesses him. You realise with delight that the Detective is not just a wily crook, putting logic to shame, but a seriously mad one as well. The pleasure of Grindley's swiftly paced production lies not just in this, but also in the nicely ham-fisted scheming of that bisexual duo, Gary Whitaker's Hal and Alexis Conran's Dennis. Tracy Ann-Oberman's Fay is far too little of the double-edged femme fatale. And Gary Richards's McLeavy ridiculously makes this spirit of lower middle class reverence for authority one class too high. But such blemishes do not much detract from the evening's pleasures - of subversive wit and low comedy in which Orton savages the hypocritical arm of the law." Nicholas de Jongh, The London Evening Standard |

"Pandering to the farcical - Joe Orton's comedies, in fact

Orton himself, holds a special place in the hearts of critics, because he

cocked a snook at the Lord Chamberlain and turned bad taste into a

fashionable theatrical commodity in the 1960s. How quaint his antics seem

in the sheep-pickling, urine-soaked, serial-killing 1990s. When Loot first

hit provincial stages, it was the use of a corpse as a comic prop that

shocked the delicate feelings of tax-paying theatregoers. Now you would

need the entire contents of the national grid to affect a similar result

on a blue-rinse audience in Tunbridge Wells. Bugger that, you can hear the

Chichester Festival producers mumbling. Let's play it for the

old-fashioned piece of farce it indubitably is. And so they do, with

results that can be neatly filed into an awful, awkward first half and a

wonderfully funny, short second half. The only guiding principle of David

Grindley's production is to turn it into one giant sketch. Stuart Wood's

design looks like a colourless doodle that has just been peeled from the

page. And the actors are so insistently intent on sending up their own

cartoon caricatures that they sound more Brechtian than Brecht. What saves

the show is Orton's truly preposterous plot, and some of the most evil

one-liners about Catholicism and police corruption in the English satiric

canon. While the freshly embalmed body of McLeavy's wife lies in a coffin

in the sitting room, his son Hal (Gary Whitaker) and his suspiciously

close friend Dennis (Alex Conran) swap the body for bank loot they have

stolen and stashed in a locked cupboard. What they haven't gambled on is

Tracy-Ann Oberman's Irish nurse. On her seventh husband and dressed up

like a saucy seaside postcard, she cashes in on the boys' predicament when

Inspector Truscott of the Yard arrives pretending to be from the

Metropolitan Water Board. "My deception was never intended to deceive

you," bellows Truscott with the delicious obtuseness of an Open University

maths professor. If Fred Ridgeway's fabulously corrupt Truscott supplies

the play-saving performance (as deranged and commanding as Basil Fawlty),

he is badly let down by his peers. The actors' banana skin accents, and

the 100mph delivery, make it sound as if no one could possibly take

Orton's jokes seriously. The whole stinging point of Orton is that his

fear of being taken seriously makes you take his fears very seriously

indeed. Comic amends are made in the second half as Truscott starts

fingering collars. But the feeling of being cheated by the farcical

convention Orton so determinedly sent up can't be flushed out of the

system by merely pandering to it. Grindley and his Chichester Festival

stooges owe us this one. At least they've got time enough now to start

delivering." James Christopher, The Times "Joe Orton was murdered in 1967. If he were still alive today he would be 65, and quite possibly Sir Joe, along with Sir Alan and Sir David and Sir Tom. What would he think, one wonders, of the latest wave of shock-horror dramatists, Irvine Welsh, Sarah Kane and the rest of them? Would he take pride in claiming them as his progeny? I like to think not - he was surely too intelligent - but one thing is certain: he would have to recognise that by current standards his own plays look relatively restrained. The power to shock is no longer an essential part of their appeal. In some respects this leaves Loot (1966) looking diminished. Much of the play's black humour turns on violating the taboos surrounding death, or the respect due to the dead; and once its first impact has worn off, it doesn't seem particularly funny - we can all read about enough unhallowed deaths in the newspapers every day. By contrast, the play's other chief element, the satire on arbitrary authority, shines as brightly as ever. Even here I think it is a pity that in revising the text, Orton left in a few touches of direct polemic against the police: polemic provokes argument. But no matter. Truscott, the mad inspector ("You're mad!" "Nonsense, I had a check-up yesterday") is a great comic creation - a master of terrifying paradoxes and sinister lapses in logic. PC Plod transformed into a grand inquisitor. Truscott isn't alone in keeping the play fresh. There is also Orton's constant feeling for the comic possibilities of language, his pointing up of cliches and inspired use of mock-pedantic precision. He was a stylist: the early admirers who compared him to Wilde were sending their thoughts in the right direction. The new production at the Vaudeville, which was first seen last month in Chichester, doesn't treat him with the finesse he deserves: in David Grindley's handling large stretches of the play come over as a kind of sitcom, Bereaved Families Behaving Badly. But the evening is redeemed, or raised to its right level, by a splendid (I was nearly going to say lifelike) performance from Fred Ridgeway as Truscott. and to a lesser degree by Tracy-Ann Oberman as a homicidal nurse intent on her next victim." John Gross, The Sunday Telegraph |

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/thr/reviews/review_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1000449399

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/thr/reviews/review_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1000449399

March

02, 2004

Journey's End

By Ray Bennett

This review was written for the production at the Comedy Theatre

in London. (Now playing at the Duke of York's Theatre through Feb. 26.)

That war is hell is not a new theme in the theater or anywhere else. That World

War I was an especially foul kind of hell also is not new, but in R.C.

Sherriff's "Journey's End," it is authentic as the play is based on the author's

own experience on the front line.

Sherriff was at St. Quentin, France, at the time of the Germans' last great

offensive of the war. He wrote the play in 1929, and so this revival celebrates

its 75th anniversary. His setting is stark, an officers' dugout less than 100

yards from the enemy front line.

In command is young Capt. Stanhope, a gifted winner in all life's races who has

been at the front "far too long" and fears that he's losing his mettle, steeling

it with whiskey. Bracing him loyally is the older Lt. Osborne, known as Uncle,

whose stalwart bonhomie steadies the men around him, especially Stanhope, as

they await the German onslaught.

Then arrives fresh-faced young 2nd Lt. Raleigh, who not only hero-worshipped

Stanhope at school but also is the brother of the captain's fiance. Terrified

that Raleigh will portray him to his sister as a drink-sodden wreck, Stanhope

fights the impulse to put the younger man in harm's way while at the same time

threatening at gunpoint another officer he believes is malingering because of

cowardice.

The tension ramps up when the company is ordered to make a raid behind enemy

lines in order to bring back a prisoner to be interrogated ahead of the coming

offensive. Two officers are to lead the raid.

This was a war of cruel paradoxes and astonishing bravery to achieve worthless

ends -- to win patches of land that would be abandoned a week later. The

soldiers were "the men," and officers were "chaps" who everyone knew would "put

on a good show." The men lived in watery, rat-infested trenches. The chaps had

cots in the dugout with a servant to cook and make tea. There was whiskey and

champagne, and when they ran out of a condiment, say pepper, a signalman could

be ordered to run down to headquarters to fetch some.

It's stiff-upper-lip stuff where being shelled every day "tells on a

man rather badly," and it's easily lampooned. In fact, Rowan Atkinson's

television comedy series "Blackadder Goes Forth" mocked it mercilessly. But here

director David Grindley gives it his full respect, and so do his actors.

Geoffrey Streatfeild is not quite shockingly young enough for the courageous but

shattered Stanhope, but he skirts cleverly close to the madness, his ashen

features and shell-shocked expressions reminiscent of a young Leslie Howard or

Robert Donat.

David Haig brings to Uncle both gravitas and a convincing acceptance of a

fellow's need to do the decent thing. Christian Coulson is suitably dashing and

appropriately dismayed by events as the new young officer, and Ben Meyjes is

persuasive as the cowardly Hibbert.

Designer Jonathan Fensom's finely detailed dugout set is claustrophobic and

unsettling: a safe haven promising imminent threat. And Gregory Clarke's sound

design is outstanding in evoking the terror outside and at the end the

horrendous clamor as the bombardment commences.

Grindley freezes his cast at the final curtain as statues in front of a wall

bearing names of the fallen. The image bears the searing austerity of genuine

memorials on the battlefields of World War I and gives Sherriff's worthwhile

play a resonance it fully deserves.

|

JOURNEY'S

END Presented by Phil Cameron for Background Credits: Playwright: R.C. Sherriff Director: David Grindley Set designer: Jonathan Fensom Lighting designer: Jason Taylor Sound designer: Gregory Clarke Casting: Sam Jones Fight director: Paul Benzing Dialect coach: Majella Hurley Music adviser: Annette Battam |

Cast: |

RC SHERRIFF’S First World War drama, Journey’s End, has often been dubbed ‘the play that swept the world’; and yet, 75 years since it first took to the stage, it has never seemed so pertinent.

The

story of men at war may hark from a bygone era of warfare, but the same sense of

futility, of loss, and of bravery against nonsensical policy, lies at its heart.

The

story of men at war may hark from a bygone era of warfare, but the same sense of

futility, of loss, and of bravery against nonsensical policy, lies at its heart.

And there really ought not to be a dry eye in the theatre by the time it reaches its shattering conclusion.

David Grindley’s excellent revival at The Comedy Theatre, in Panton Street, may have been put on to mark the anniversary, but it also proves an adept piece of commentary.

Its message is clear. The art of warfare may have changed; but the consequences remain the same, and the tragedy is no less wasteful.

The play is set in the days before one of the most intensive German offensives of the First World War, which took place on March 21, 1918, at St Quentin in France, as a group of officers contemplate the impending conflict, and what has gone before.

Led by Geoffrey Streatfeild’s courageous Captain Stanhope, the officers must prepare themselves for the grim inevitability of what lies ahead, as well as coming to terms with the arrival of an eager young recruit, Christian Coulson’s earnest Raleigh, a newly commissioned second lieutenant, who wants nothing more than to serve under (and impress) his former schoolmate, Stanhope.

But whereas Raleigh is a fresh-faced idealist, new to the trenches, Stanhope is a man twisted and broken by war, a pale imitation of his former self, who relies on a whisky bottle to get him through the day, and who happens to be dating Raleigh’s sister.

It is his very real fear that Raleigh’s ‘hero worship’ might turn into disgust, and that letters home may inform his 'woman in waiting' of the changes that have taken place to the man she once knew.

Attempting to reassure him to the contrary is David Haig’s level-headed Osborne, who operates as the heartbeat of the company, while rounding out the cast are the likes of Phil Cornwell’s comic cook, Mason, and Paul Bradley’s overweight officer, Trotter.

The ensuing drama unfolds at a deliberately slow pace, so as to accentuate the impending sense of dread that hangs over the men, while also cranking up the tension to an almost unbearable level towards the end of the second act.

And yet, throughout, proceedings are infused with a nice line in humour, which punctuates the heavier, more emotionally involving elements of the story.

Grindley also pulls a neat trick by allowing the viewer to form their own conclusions - his direction is subtle, even minimalist, at times, especially during an ill-fated raid, in which the audience is left to stare at an empty stage, as the sound of bombing and machine gun fire reverberates around them, allowing their imaginations to run riot.

In an age where the need to show everything in gory, graphic, often slow-mo close-up at the movies over-rides everything, this is an effective reminder of how less can often provide so much more.

It serves to heighten the poignancy of the scenes which come before it, while providing an effective platform for Streatfeild’s Stanhope to breakdown, once the fallout becomes apparent.

Credit, too, deserves to go to Grindley for refusing to become too manipulative. The scenes speak for themselves, such is their power, yet even the Germans are shown to have a human side.

This is a battlefield in which the distinction between good and bad is lost, and only confusion remains.

And it is best illustrated during a monologue in which Haig recalls a moment when a German captain ceased fire to allow the British to carry a critical soldier to safety - before both sides proceeded to blow the hell out of each other on the following day.

This is first and foremost about loss, about sacrifice (both old and young), and about the futility of war.

Of the exemplary performers, Haig probably shines the brightest, providing a deeply affecting father figure to Stanhope and a moral guide to everyone around him.

When Stanhope loses his temper, it is Osborne people turn to for reason, and when advice, or companionship, is needed, it is generally Osborne who provides it.

Needless to say, when he is selected as one of the two officers who must lead the aforementioned raid, the hopelessness of his situation is cleverly and effectively portrayed.

His final scenes with Coulson's Raleigh are among the most emotional I have had the good fortune to see at the theatre for some time. And yet they never become showy in a way that a higher profile actor may have attempted to make them.

But Streatfeild, too, isn't far behind Haig in the performance stakes, flitting between heroic leader and drunken despair with aplomb, and turning his complex Stanhope into a genuinely affecting character.

His final scenes possess a power which smacks home with all of the intensity of one of the bombs which seem to fly over our heads during the final battle 'sequence', and it is his final reaction to the plight his men face that ensures this is a play which will tug at the tear-ducts.

And yet as powerful and heartbreaking as Journey's End is, there is an inspiring element to its anti-war message; one which makes you glad to be alive and grateful to have seen such a mesmerising piece of theatre.

It is, without doubt, one of the finest productions I have seen in the theatre, and one which ensures that, years from now, we shall still remember them...

Journey's End, by RC Sherriff. Directed by David Grindley.

Starring David Haig, Geoffrey Streatfeild, Christian Coulson, Phil Cornwell,

Paul Bradley. The Comedy Theatre, Panton Street, W1. Seat Prices:

£37.50, £34.50, £27.50, £22.50, £15.00. Thursday matinees £22.50 for best

available.

Playing until: May 1, 2004

|

| Toby Kebbell, Pearce Quigley and Paul Bradley in Journey's End at The Playhouse Theatre. Photo: Geraint Lewis |

It says much for the strength of David Grindley’s production that I remained riveted, as did all the audience, throughout Journey’s End, despite the fact that it is only four months since I last saw it.

Moreover, RC Sherriff’s play, though sometimes derided for its outmoded attitudes and speech patterns in its previous post-World War II revivals, proves that it is not only a masterpiece in its own right but is an absolute model of play construction. Apart from the fact that not a word is wasted, observe the way in which Sherriff sets his first scene, introducing all the main characters in their absence, and calmly builds up to the climax without destroying any of the shock when it finally arrives. It is Grindley to whom we owe the incredibly moving curtain call, the most stunning within living memory.

The transfer from the Comedy has brought in several new faces, most of them previously unknown and with surprisingly little experience. David Sturzaker is a superb Stanhope, only 21 but one of the most experienced company commanders in the front line, and Toby Kebbell is the 18-year-old new boy, fresh out of the same school that Stanhope attended and still full of hero worship.

Praise too for the other younger replacements, Ifan Meredith’s Hibbert, the coward with whom we can reluctantly sympathise, and Pearce Quigley as the stoic cook. Bringing experience and wonderful understanding to the role of the fatherly Osborne is Philip Franks and Paul Bradley continues his warm and amusing study of the ex-ranker Trotter.

The British premiere of a drama set in 80’s suburban Detroit in a real-time drama that lays bare the American dream. National Anthems tells the story of Arthur and Leslie Reed, an affluent couple whose delightful house is packed with swanky imported furniture and designer clothes and who have a brand new BMW out the front and an ornate Japanese garden round the back. Everything is going absolutely delightfully until Ben Cook - an inner city fire fighter arrives to add a little spice to their 1980’s idyll.

This description of the play sounds interesting enough. Critics, though, say it's more medicore than interesting, and, though some commend the actors for doing their best in an uphill struggle, no one cares much for the play (some even label it worse than Cloaca, Kevin Spacey's first venture as Old Vic artistic director).

Charles Spencer (Telegraph):

"I find myself worrying about Kevin Spacey. When he took over as the Old Vic's artistic director and announced that his first two major productions would be new plays, I raised a sceptical eyebrow. New plays are notoriously risky propositions.

"Spacey, however, insisted that the scripts he had chosen were absolute corkers, and it was impossible not to warm to his courage and enthusiasm.

"Unfortunately the first play, Maria Goos's Cloaca, flopped on to the stage with all the allure of a faintly rancid dead fish, and after a brief break for Ian McKellan's enjoyable turn as Widow Twankey in Aladdin, Dennis McIntyres's National Anthems proves another dud.

"It is sparkily acted, with Spacey in particular delivering a splashy star turn. But the play feels shallow, contrived and dated.

"Though National Anthems is receiving its British premiere at the Old Vic, it was first seen in the States in 1988, when Spacey also played the leading role. The play is a satire on the 'greed is good' culture of the late 1980s, but the subject matter seems strangely irrelevant at a time when America is engaged in far more dangerous adventures.

"Times have changed, and it seems bizarre to revive this parochial little play when the stakes are so much higher, and much more than capitalism is red in tooth and claw.

"The action is set in a posh, white suburb of Detroit, in the new dream home of Arthur and Leslie Reed, an archetypal yuppie couple (remember yuppies?). He's a lawyer, she teaches at an expensive private school, and they are just clearing up after a house-warming party.

"Then Ben Cook (Spacey) arrives, uneasy amid the luxury, unmistakeably blue collar though he lives nearby. The couple reluctantly invite him in, patronise him, boast about their possessions. Arthur in particular can't mention anything without also revealing how much he paid for it.

"Tensions rise, as Spacey, a fireman who has recently saved a black woman's life in a terrible blaze, spills his drink on the new carpet and insists on embarrassing party games. And by the second act the two men are playing a vicious game of American football in the luxurious living room, and beating eight bells out of each other.

"The trouble is that it all proves so predictable and obvious. As soon as I saw Jonathan Fensom's plush set, I guessed it would be trashed before the evening was out, and McIntyre, who died not long after the play was first produced, never trusts the audience to draw its own conclusions.

"The ghastly Arthur isn't allowed a single redeeming feature, the heroic fireman, pushed to the margins of society by greed, is presented as a tragic hero. The dramatist's editorialising portrayal of racism and class conflict often seems more like a political pamphlet than a play.

"David Grindley, who directed such a fine production of Mike Leigh's not dissimilar though vastly superior Abigail's Party, gets the most out of the jokes but can't conceal the glib nature of the play, while his staging of the violence proves far too tame.

"Spacey is initially charismatic and unsettling as the troubled fireman but is reduced to an embarrassing solo turn of blubbing sentimentality by the end. Steven Weber nails the vile Arthur with slick precision, but finds no hints of dramatic depth, and Mary Stuart Masterson as the house-proud wife only comes fully alive in a disconcertingly sexy cheer-leader routine.

"I hate putting the boot into the Old Vic for the second time, for Spacey's project is a noble one. But let's see him in Shakespeare and bona fide American classics, not mediocre fare like this."

Benedict Nightingale, Times, two stars:

"WHAT’S happening at Kevin Spacey’s Old Vic?

First, his regime staged Cloaca, a doleful Dutch play about the male

menopause. Then came Aladdin, which let Ian McKellen frolic about in a

series of pantomime frocks. And now here’s the British premiere of Dennis

McIntyre’s 1988 play about Detroit suburbia and Michigan macho, with the

artistic director himself roaring through a sedate living room trying to

recapture his form as a promising high-school football player.

"Has Spacey yet got his finger on the pulse — or at least on a pulse that

matters to us in England? From the moment I entered the Vic, to see a vast Stars

and Stripes covering the stage in a rather big hint of the evening’s tenor, I

began to wonder, and when the flag collapsed to reveal the innards of one of

those overblown doll’s houses you find all over middle-class America, I wondered

some more. By the time David Grindley’s production had reached its supposedly

poignant end, I was still wondering.

"Well, let’s not be insular. We, too, suffer from boastful consumerism, which is the theme of the first act. Spacey’s Ben, you see, is a fireman, owns the smallest house on the block, and isn’t too comfortable when he comes to introduce himself to the latest arrivals. That’s especially so since neither Steven Weber’s slick Arthur Reed, a lawyer specialising in tax havens, nor his Stepford-style wife, Mary Stuart Masterson’s Leslie, can stop talking about their smart, monied friends and their foreign possessions: Italian furniture, Danish sound system, even a German tray.

"McIntyre has his subtler moments, as when he evokes the cracks in the Reeds’ nice-seeming marriage, but the play veers too far towards caricature and doesn’t veer very far back in the second act, when male competitiveness and nostalgia for lost youth become the subjects.

"Suddenly the men are recalling their footballing days in, respectively, Pittsburg and Detroit and, after a mildly ferocious exchange of insults and threats, decide to stage a crunch match between the Milanese sofas. Crash, bang — and Spacey the loser emerges Spacey the winner.

"For a moment all is calm and it looks as if another American genre, the buddy play, is in the offing. But no. Being a rich, rising corporate lawyer, Arthur turns mean, nasty and racist, mocking Ben’s one claim to fame, which is that he has just rescued a black woman from a burning welfare hotel in downtown Detroit. And so to a denouement — a retreat into fantasy, a nervous breakdown, or both — that Spacey has to use all his skill to make even slightly plausible.

"Still, his is a highly skilful performance, whether he is defensively babbling or forlornly blustering or remembering his heroics or, all too occasionally, injecting a sly, funny put-down into the unequal chat.

"With Weber exuding gogetting aggro, and Masterson doing all she can with an unrewarding role, the acting isn’t the problem. But the choice of play is. "

Paul Taylor, Independent:

"Last autumn, Kevin Spacey's artistic directorship of the Old Vic was launched with Cloaca , a play that hit the stage with all the lustre and vibrancy of a bag of stale bread. It seemed then that up was the only direction in which his regime could go.

"Now, after a pantomime parenthesis, the season continues with National Anthems, a three-hander by Dennis McIntyre in which Spacey reprises a role he first performed in a 1988 production of the play in New Haven, Connecticut. His programming of this rare revival (staged by an English director, David Grindley) indicates that he thinks that the play deserves rescuing from neglect. Is he right?

"Well, it's a bit of a sideways move from Cloaca, actually. The piece is more effective as a slick and sometimes wincingly contrived showcase for Spacey's acting talents than as the savage satire on late-Eighties materialism in America that it's cracked up to be.

"The star plays Ben Cook, a fireman who drops in unannounced on an affluent couple (Mary Stuart Masterson and Steven Weber) who live next door to him in a new Detroit suburb as they're clearing up after a party. Spacey has a lot of broad fun early on portraying the kind of overbearingly friendly and ineffably subversive neighbour that you would organise a neighbourhood watch to protect yourself against.

"There's underlying darkness, natch. It turns out that Ben recently saved a woman's life by pulling her from a burning hotel. But this courageous feat has got him the sack because it came about by disobeying orders..

”He's an unemployed hero only for a day in the local free press and his Yuppie attorney host (lean, mean Weber) makes the most of this pathetic predicament, when he comes off worst in a one-to-one American football match which he plays with Ben in the lovely living room.

"The living room? Why don't these guys just drive out to a park? Because it's the author's idea of a neat irony to have the values of fetishistic materialism and virile self-assertion clash in such highly artificial circumstances.

"Spacey gets to strut about comically as a reborn football champ and then crumple tragically and veer into madness as the attorney delivers one viciously bigoted blow after another.

"Ben's bravery, he insists, does not count in worldly terms because the woman was black and because the hotel was a residence for people on welfare. He's a loser period.

"The character also comes across as a set of performance opportunities rather than a real person. Despite the huge stage-draping American flag that flutters to the floor at the start of Grindley's polished production, the play never persuades you that it attains the symbolic dimensions aimed for in the title.

"And up is still the only direction in which this weird regime can move. "

Michael Billington, Guardian, three stars:

"Kevin Spacey is at last back where he belongs: on the stage of the Old Vic. After the dismal start to his artistic tenure here with the play Cloaca, he now stars in Dennis McIntyre's play which he first performed at the Long Wharf Theatre, New Haven, in 1988.

"But, while Spacey is mesmerising to watch, McIntyre's play offers a glibly mechanical metaphor for American life. Spacey plays an uninvited guest who one Saturday night invades the home of a neighbouring yuppie couple, Arthur and Leslie, in suburban Detroit.

"Plying his hosts, who are just recovering from a party, with questions, Spacey's apparently beneficent Ben quickly learns all the secrets of his neighbours. He's a lawyer, she's a teacher. Everything, from their hi-fi to their garden, is a swish foreign import. And their friends are all comparable high-flyers including Arthur's boss who's a world-class ice-boater.

"McIntyre sets the situation up nicely with Ben as the catalyst on a hot suburban rug destined to expose the cracks in the American dream. And, up to a point he does, challenging the highly competitive Arthur to a series of games which Ben invariably wins.

"But, with the revelation that Ben is a fireman lately involved in a brave rescue, the play takes a severe downward turn. McIntyre establishes Ben as an enigmatic eccentric reminiscent of Priestley's Inspector Goole. He then, by a devious narrative switch, turns into him into a symbol of heroic, if troubled, ordinariness.

"On the sheer level of plausibility, the play doesn't make total sense: why, you wonder, would the snotty Arthur beg this unwanted gatecrasher to stay? And when the two men engage in a bout of macho bragging about the respective toughness of Detroit and Pittsburgh football players and prove their point on the living-room floor, the contrivance is palpable.

"Even worse is McIntyre's misogynistic treatment of Leslie who reverts to her old role of cheerleader and blithely switches her affections to the contest's winner.

"I'm all for plays that take apart American values. But where Edward Albee's Who's Afraid Of Virginia Woolf turns a living room into a national metaphor by laying the psychological groundwork, McIntyre treats his characters as off-the-peg symbols. The moment you see Arthur fiddling with his game watch, you know he is meant to represent modern materialism. Leslie, fussily tidying up while spouting Japanese phrases from her Walkman, is instantly labelled as the embodiment of aspirational chic.

"But, even if McIntyre's play fails to deliver, it creates a fine part for Spacey. And he succeeds in investing Ben with a faintly manic strangeness. Outwardly, with his receding hairline and moustache, he looks like an average guy. But when he learns that Arthur and Leslie have been married for nine years, he claps his hands with mockingly ostentatious delight. Told that Arthur's watch cost $7,200, Spacey announces 'you really know what time it is, don't you?' with a guttural Grouchoesque drawl.

"Spacey doesn't just occupy the stage, he seizes it by right. And, even in the stagey football contest, he is devastatingly funny. 'Detroit,' he swaggeringly proclaims, 'doesn't have football, it has ballet.' And when he tackles and fells his host, he jives and dances around his prostrate form with insulting hip-twitching gestures.

"Spacey is an actor who enjoys acting. But precisely because he is so sly, ironic and smart in exposing Arthur's macho fatuities, it becomes hard to swallow the character's descent into neurotic normality.

"Attentive though it is to suburban detail, David Grindley's production cannot disguise the play's awkward gear change. And Steven Weber and Mary Stuart Masterson as Arthur and Leslie do what they can to camouflage the fact that they are playing national symbols. Weber lends the feverish Arthur a restless tension though the character is mainly a monster in an Armani suit. And Masterson uses all her technique to lend depth to a character that's a male dramatist's fantasy.

"But the evening belongs to Spacey. And I would simply beg him, as the Old Vic's artistic director, to bombard us in future with masterpieces. There is a wealth of work in which one would love to see him: Shakespeare, Ibsen, O'Neill, Mamet, the great American comedies. In McIntyre's play he gives a dazzling performance but he looks like a great boxer in an exhibition bout."

Nicholas de Jongh, Evening Standard:

"I begin to have serious doubts about whether

Kevin Spacey is the right man to run the Old Vic. He launched his regime as

artistic director last autumn by presenting a dud Dutch drama about miserable,

middle-aged men discharging emotional waste about the stage.

"He caps that dire experience with an even more boring, almost interest-free

event. Dennis McIntyre's National Anthems, a minor comedy that finally

slithers into melodrama's gulch, mounts a flaccid, sentimental assault upon

materialism and a values system that over rewards the university-educated at the

expense of heroic, blue-collar public servants. Playwrights have made such

indictments before. McIntyre had little fresh to add to the old charge sheet.

"The play is set in 1988, the year of its Connecticut premiere, with Spacey its star then as now. First the American flag, serving as a curtain, collapses in a vaguely symbolic gesture. A miscast, goateed Spacey, mustering a few flashes of conviction as Ben Cook, a sad, middle-aged American fireman, effects an entrance into the suburban, Detroit home of his new neighbours, the Reeds.

"Mr Spacey peddles a line of perky, pushy self-confidence, that makes light of his character's underlying despair and isolation. At the climax, when charges of racism are in the air and Cook is verbally abused, Spacey charges into a hysterical re-enactment of Ben's fire-fighting heroism with all the raging enthusiasm of a bull charging a red rag. David Grindley's production lacks the dimension of subtlety.

"Spacey's initial, aggressive, streetwise air seems less that of a fireman trying to make a social impression than an actor putting on the wrong show. Steven Weber's insipid, tax attorney, Arthur Reed, wearing a two-piece suit and one-set expression and Mary Stuart Masterson's teacher-wife Leslie in a scarlet dress, whose skimpiness at the crotch exudes an air of never justified erotic promise, are as dull a young couple as any you could mischance to meet on a Saturday night.

"In the real world, rather than the contrivances and make believe of National Anthems, you can bet a million dollars the smart couple, tired after a party, would have shown Ben the burglar-proof door in a few icy minutes. Instead they keep him there for empty chat.

"The living room, according to the text, is supposed to look beautiful and subtle. Lacking knowledge of what passes for beauty in Detroit leaves me unable to comment. Smart consumer stuff and status symbols, from Rolexes and Porsches to Bang and Olufsen speakers are duly, dully reverenced by Ben.

"The fireman, details of whose married life are left oddly unmentioned, increasingly emerges as a pathetic hero, penalised despite saving a woman's life in a fire, his bravery relegated to a small item in a free newspaper.

"Spacey, however, wears the status of victim to the manner unborn. He is far more at home with situation comedy: the scenes of Ben's knee-slapping parlour game, his spilling of alcohol on Arthur's jacket and a carpet, the two items worth almost $11,000, injects notes of comic relief and embarrassment.

"The impromptu game of American football played by the two men tips the action towards violence and Arthur towards the gratuitously cruel dismissal that sends Bob into a frenzy. The extravagant finale does not,though, give this supine drama a lift from the doldrums where it lies anchored."

Masterson, who plays Leslie Reed, appeared on Broadway last year opposite Antonia Banderas in Nine, for which she received Tony, Outer Critics’ Circle and Drama Desk nominations, as well as a World Theatre Award. She’s best known for her screen credits including Fried Green Tomatoes, Benny and Joon, Some Kind of Wonderful, Radioland Murders, Bad Girls and The Stepford Wives.

Weber, who plays Arthur Reed, has appeared on Broadway in Loot, The Real Thing and as Leo Bloom in The Producers. His US film and television credits include Leaving Las Vegas, Single White Female, Hamburger Hill, Wings, The Shining and Reefer Madness.

http://www.curtainup.com/nationalanthems.html

http://www.curtainup.com/nationalanthems.html

The Internet Theater

Magazine of Reviews, Features, Annotated Listings

A

CurtainUp

![]() London Review

London Review

National

Anthems

by

Lizzie Loveridge

|

| Kevin Spacey as Ben, Mary Stuart Masterson as Leslie and Steven Weber as Arthur. (Photo: Manuel Harlan) |

Dennis McIntyre's 1988 play National Anthems is the

third to be staged by the new regime at the Old Vic under actor-artistic

director Kevin Spacey. It is undoubtedly a showcase for Spacey's considerable

stage talent which some of us were fortunate to see in The Iceman Cometh

when he all but cleaned up the major London acting awards. But and here's the

rub, Dennis McIntyre was no Eugene O'Neill. However the play does have some

serious points to make about the materialism of late twentieth century society

at the expense of humanity, and the acting throughout is superb.

A huge flag, the stars and stripes, the quintessential symbol of things

American, is hung across the stage like a makeshift stage curtain. Here I am

sitting two seats away from Pierce Brosnan and about to see the great Kevin

Spacey onstage. You can forgive me for thinking that I have died and gone to

heaven. A parallel strikes me, National Anthems has more product

endorsements than the latest James Bond films. The set is wonderful: the sitting

room of a large American house with Italian leather sofas and designer

furniture. The windows are swagged and swathed in what interior designers

curiously describe as window dressing, not curtains you understand but pieces of

fabric twisted and pleated and draped around three sides of the window, pure

ornament.

Set in Detroit's suburbs in the home of aspiring middle class couple, Leslie and

Arthur Reed (Mary Stuart Masterson and Steven Weber), National Anthems

contrasts the life of these "yuppies" with that of their uninvited party guest,

fireman Ben Cook (Kevin Spacey). Ben has less money, fewer social contacts than

the Webers who are ostentatious about their imported porcelain, their Irish

linen, their German cars, their Danish Hi Fi system . However Ben has his

fifteen minutes of fame in an article in the newspaper about his disobeying

orders to rescue a woman from a blazing building.

When McIntyre strips his characters down to their bare bones, both men are very

competitive; like sportsmen they have an overpowering desire to win. Weber, the

tax haven lawyer in his nineteen hundred dollar suit, plays a relentless game

eventually crushing Ben Cook. Although the two men recreate tackles on the

football field, it is words which deliver the final blows to Cook's self esteem.

Directed by David Grindley who was responsible for the revival of that 1977

English play about social mores, Mike Leigh's Abigail's Party,

National Anthems is less tragic, less cathartic and less bitingly comic but

less dated.

The upside of this play is some wonderful acting. Spacey is mesmerising whether

gossiping and divulging intimate details about the neighbours or fast talking in

the quick response drinking game, "The Name of the Game is …" or when facing

full on to the audience, slowly masticating a shrimp puff and staring out at us

vacantly and round eyed. Steven Weber is strung, every sinew bristling with the

need to be first, unpleasant as only lawyers can be. Mary Stuart Masterson is

almost wasted here. Her role as Leslie is to be very, very nice in that anodyne

society hostess way but she comes to ridiculous life as a caricature high

kicking cheerleader when supporting her husband's football moves. "Just bring

home the dream Arthur", she says. At the end of the play Leslie partially

explains her own insecurity, the background to why she has to keep everything

clean and pristine in the house.

The men in a comic dialogue try to best each other's anecdotes of just how tough

college football was whether in Cook's Pittsburgh or Reed's Detroit. The comedy

is pretty near the surface for most of the play but the tragic end is not just

Ben Cook's but also for the Reeds. Arthur realises how dead his life is now

compared to when he played ball and listened to the music of Credence Clearwater

Revival and the Stones.

The exciting news at the Old Vic is that Jennifer Ehle will play Tracy Lord to

Spacey's Dexter in the upcoming revival of The Philadelphia Story from

the beginning of May and that next season Spacey will play Richard II

directed by Trevor Nunn.

|

National Anthems

Starring: Kevin Spacey |

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/arts/4249275.stm

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/arts/4249275.stm

Press

views: National Anthems

Actor

Kevin Spacey is treading the boards at London's Old Vic theatre for the first

time since becoming its artistic director. The Oscar-winning star is appearing

in National Anthems as a blue-collar worker in 1988 Detroit at odds with his

yuppie neighbours.

|

| Spacey plays middle-aged fireman Ben Cook (pic Manuel Harlan) |

THE

GUARDIAN - MICHAEL BILLINGTON

Kevin Spacey is at last back where he

belongs: on the stage of the Old Vic. After the dismal start to his artistic

tenure here with the play Cloaca, he now stars in Dennis McIntyre's play which

he first performed at the Long Wharf Theatre, New Haven, in 1988. But, while

Spacey is mesmerising to watch, McIntyre's play offers a glibly mechanical

metaphor for American life. The actor gives a dazzling performance, but he looks

like a great boxer in an exhibition bout.

I would simply beg him, as the Old Vic's artistic director, to bombard us in

future with masterpieces.

THE

INDEPENDENT - PAUL TAYLOR

The piece is more effective as a slick and

sometimes wincingly contrived showcase for Spacey's acting talents than the

savage satire on late-Eighties materialism in America that it's cracked up to

be. Spacey gets to strut about comically as a reborn football champ and then

crumple tragically and veer into madness.

But the character comes across as a set of

performance opportunities rather than a real person. Despite the huge

stage-draping American flag that flutters to the floor at the start of David

Grindley's polished production, the play never persuades you that it attains the

symbolic dimensions aimed for in the title.

THE DAILY

TELEGRAPH - CHARLES SPENCER

National Anthems is sparkily acted, with

Spacey in particular delivering a splashy star turn. But the play feels shallow,

contrived and dated. The play is a satire on the "greed is good" culture of the

late 1980s, but the subject matter seems strangely irrelevant at a time when

America is engaged in far more dangerous adventures. David Grindley gets the

most out of the jokes but can't conceal the glib nature of the play.

Spacey's project at the Old Vic is a noble one.

But let's see him in Shakespeare and bona fide American classics, not mediocre

fare like this.

THE DAILY

MAIL - QUENTIN LETTS

National Anthems (poor title) is fluent,

funny, an easy watch with several clever lines. The set is opulent, the acting

more perfect than the casting. Mr Spacey is on fine form. He has the waxy face,

clunky shoulders, the 'let me tell ya something!' relentlessness that can make

suburban bores such social terrorists. In places this comedy of refined manners

makes this an American Abigail's Party. Artistically this is not quite the hit

Spacey's regime at the Old Vic craves. That will not stop London trendies

enjoying it enormously.

http://www.nowt2do.co.uk/TPreview_Some.htm

http://www.nowt2do.co.uk/TPreview_Some.htm

Nowt2Do.Com Theatre Preview

Name: Some

Girls

Venue: The Gielgud Theatre, London

Dates: From May 12th 2005 to 13th August 2005

How to book: Call

0870 890 1105.

![]()

DAVID

SCHWIMMER

TO STAR IN THE WORLD PREMIERE OF

“SOME GIRL(S)”

A NEW PLAY BY NEIL LABUTE

AT THE GIELGUD THEATRE

PREVIEWING FROM 12 MAY

David

Schwimmer

will star in the world premiere of “SOME GIRL(S)” a new

play by the controversial American playwright and film-maker Neil LaBute.

Directed by David Grindley, the play will preview at the Gielgud Theatre

in London from 12 May, with a press night on 24 May. The show marks American

film and television actor David Schwimmer’s West End stage debut. Further

casting will be announced at a later date.

David

Schwimmer

will star in the world premiere of “SOME GIRL(S)” a new

play by the controversial American playwright and film-maker Neil LaBute.

Directed by David Grindley, the play will preview at the Gielgud Theatre

in London from 12 May, with a press night on 24 May. The show marks American

film and television actor David Schwimmer’s West End stage debut. Further

casting will be announced at a later date.

In love, if you wait for second chances, you could be waiting a long time. Wouldn't it be simpler just to schedule all those chances into one quick trip...? David Schwimmer makes his West End debut in the world premiere of Neil LaBute's biting new comedy “SOME GIRL(S)” - an irreverent stumble into the heart of darkness that is the modern single male.

Writer, director, and playwright Neil LaBute’s plays include “The Mercy Seat”, written and directed by LaBute in Autumn 2002 in New York starring Sigourney Weaver and Liev Schrieber; “The Distance From Here”, written by LaBute, which ran at the Almeida Theatre in London in Spring 2003 and spring 2004 in New York; “The Shape of Things” which LaBute wrote and directed for London and New York in 2001, and which recently completed a revival staging in London at a the New Ambassadors Theatre; and “bash: latter-day plays”, which LaBute wrote and directed for New York and London in 1999. This March, his latest play, “This Is How It Goes”, will premiere at New York’s Public Theatre and will be directed by George Wolfe. In May, the play will debut in the West End at the Donmar Warehouse. Films include “In the Company of Men”, which won the New York Critics’ Circle Award for Best First Feature and the Filmmaker’s Trophy at the Sundance Film Festival; “Your Friends & Neighbors”; “Nurse Betty”; “Possession”; and “The Shape of Things”, which was a film adaptation of his play by the same title. He is also the author of several fictional pieces that have been published in “The New York Times”, “The New York Times Magazine”, “Harper’s Bazaar”, and “Playboy” among others. “Seconds of Pleasure”, a collection of his short stories, was published by Grove Atlantic in October 2004.

Internationally known for his Emmy nominated role as ‘Ross Geller’ in the US TV series "Friends", David Schwimmer studied theatre at Northwestern University, before founding the acclaimed Lookingglass Theatre Company in Chicago - an ensemble for whom he continues to act, direct and produce.

His stage-acting credits with Lookingglass include "The Idiot”, “Arabian Nights”, “West", "The Odyssey", "Of One Blood", "In the Eye of the Beholder" and "The Master and Margarita". His stage-directing credits include "The Jungle", which earned six Joseph Awards; his adaption of Studs Terkel's book “Race”: "How Blacks And Whites Think And Feel About The American Obsession" and "Alice in Wonderland", which was performed at the Edinburgh Festival in Scotland.

He has also starred in the stage premieres of Roger Kumble’s “D Girl” and "Turnaround" in Los Angeles, and in Warren Leight’s “Glimmer Brothers” in Williamstown. As well as his role in ten years of "Friends", Schwimmer has also starred in Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg's mini-series “Band of Brothers”, in “Hotel”, a dark comedy from Mike Figgis and “Uprising”, the NBC miniseries about the Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto. Other television credits include roles on such series as “Monty” with Henry Winkler, “NYPD Blue”, “The Wonder Years” and “L.A.Law”.

His feature film credits include the independent feature “Duane Hopwood”, which premiered at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival, “It’s the Rage”, with Gary Sinise, Giovanni Ribisi and Joan Allen, “Picking Up the Pieces”, “Six Days, Seven Nights”, “Apt Pupil”, “Kissing a Fool”, “The Pallbearer”, “Crossing the Bridge” and the critically acclaimed HBO film “Breast Men”. He also directed the feature film “Since You’ve Been Gone” for Miramax, and has directed episodes of “Friends" and spin- off series "Joey".