The

Observer, 3 April 2005

The

Observer, 3 April 2005Interview

'I'm a risk-taker, there's no doubt about it'

Sally Greene

The

Observer, 3 April 2005

The

Observer, 3 April 2005I NEVER CEASE to be amazed by how little the rich and famous eat. Sally Greene, reviver and runner of ageing theatres extraordinaire, also happens to own with her husband, the extremely wealthy property developer, Robert Bourne, a brasserie in a discreet corner of Chelsea. It's a lovely looking place, a former pub that has been fitted out with leather banquettes in duck-egg blue, extravagant lighting and a great, big, wood-burning grill smack bang in the middle of the room.

Greene has chosen this brasserie for our meeting (against my wishes: usually, I am too greedy to be able to ask probing questions and scoff lunch at the same time) and yet, now the two of us are ensconced at our corner table, her appetite seems almost non-existent. First, she chews on a couple of raw carrots. Then she picks the meat off a chicken leg. 'Oh, this is delicious,' she cries, nibbling delicately. 'Oh, it's really very good.'

But perhaps she has a nervous knot in her stomach. As per usual, Greene has about a dozen balls up in the air and at least one of them has come whizzing towards her with inordinate speed. Last week, Billy Elliot, the multimillion-pound musical version of the film (with songs by Elton John), of which she is a co-producer, finally began previewing at the Victoria Palace.

'I've never seen anything like it in the West End before,' she says. 'It's a different kind of musical. I get a real high when I'm watching it. It's about the Eighties, the miners' strike, Maggie Thatcher, Michael Heseltine... Stephen [Daldry] is a magical director. He sprinkles this magic dust all over his shows. Last year, we had a workshop [for the show] at the Old Vic. Elton came over on his plane, and he said he flew all the way back to France without it, he was so excited.' A smash hit, then? 'Of course!'

Meanwhile, the rest of her empire continues to throb and swell like a great blob of warm dough. Over at the Old Vic, which Greene owns, the box office is still defying the critics, as audiences crowd in to see Kevin Spacey, the theatre's artistic director, star in National Anthems. At Wyndham's, she is about to stage yet another production of The Vagina Monologues, this time starring Sharon Osbourne. Oh yes, and she has recently bought Ronnie Scott's, the Soho jazz club. Her plans for it include a new bar 'for talking', and a full-throttle attack on its fearsome food, of which Ronnie Scott himself once said: 'A thousand flies can't be wrong.'

|

|

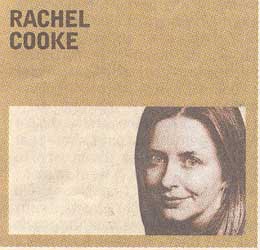

Sally Greene: 'You do need an element of madness.' Photograph by Linda Nylind |

DOESN'T SHE ever worry that she has taken too much on? Is she, perhaps, just a little bit mad? She honks with laughter (it is disarming, this honking, though I suspect that it is just one cloak in a whole dressing room of techniques designed to keep my sticky beak at bay).

'You do need an element of madness,' she says. 'I am a risk-taker, there's no doubt about it. It's bloody risky. You spend an awful lot of money, and then you're at the mercy of the critics. But you think about today; you don't think too much about tomorrow. I'll tell you what it is: on the inside you're calm, and on the outside, you're buzzing. So it belies what you feel inside. If anything does get too much, too outrageous, I let myself go calm inside, even though on the outside I might be this buzzy woman. It's an art; you learn it.'

I look at her carefully. To me, she seems quite buzzy now - girlish and excitable. Does this mean that inside there lurks a cool lake into which she might dive at any moment? It is quite impossible to tell.

Greene will talk about pretty much anything, although only if she is permitted to use words like 'terrific', 'wonderful' and 'brilliant'; the bad stuff - those mean-spirited critics, those terrible rock musicals that squat likes toads in theatres for years upon end - she would rather not get into. (She may have given up her acting career aeons ago but, in this sense at least, she is still very much a luvvie.) In order to avoid controversy, she will not even leap to the defence of her friend Spacey, who has had a particularly hard time of it with the press (his first play at the Old Vic, Cloaca, is generally agreed to have been a stinker).

When I bring his name up - and, after all, it was Greene who managed to persuade him, over lunch, to take on the job in the first place - she taps my tape recorder with a pretty fingernail. 'Turn it off,' she says. She then explains that she will not discuss Kevin at all. He does his own press. If I want to talk to him, she might be able to arrange it. But she would rather talk about Billy Elliot which, as she has already told me, is just, well, fantastic.

GREENE'S FAMILY STORY reads like it has strolled straight out of the pages of a dusty novel by Noel Streatfield. Her paternal grandfather, Sidney Greene, was an actor. 'My father loved telling us this story. Sidney was playing at the Haymarket, and when the lead left, he wasn't offered the part, even though he was the understudy. So he was very upset and accepted a tour of Australia. In those days, you went to the boat by train. My grandmother and her two sons, including my father, went to Victoria to wave goodbye. But when they got there, they saw a carriage that said "Mr and Mrs Greene".'

So he had bolted with his mistress? 'Yes! They never saw him again, except when there was a tiny column in an Australian newspaper announcing that a British actor had died, aged 52. My poor grandmother. She was a dressmaker. They'd had quite a luxurious lifestyle, but you know how designers go out of fashion. Things changed. Only my father went to boarding school. Uncle Ronnie had to stay in London,' she sighs.

Her father was a lawyer who loved the theatre and wrote plays in his spare time: 'My God, they were the most awful plays, but he always put in a part for a young girl, which was me.' Her father was a cheery soul, but her mother was a depressive. The marriage was not very happy. 'My mother was very religious. She was one of 12 and practically every one of them was a priest or a nun. We said the rosary every night. I would giggle all the way through it. I didn't get on with my mother. I didn't get on with Catholicism, all that guilt it conjures up. I hated convent school. I was disruptive. I was always in trouble. I couldn't wait to escape.'

Drama school - she attended the Guildhall and then 'one of those weird postgraduate places where we improvised everything' - brought her out of herself, but she knew almost from the beginning that she would never make it. 'I was the worst actress in the world - ever,' she says. 'I knew I wasn't very good. I'm interested in being the proactive person. I don't want to walk into a room and just be judged on what I look like.'

It was while appearing opposite Peter Ustinov in a play called Beethoven's Tenth in Brighton that she realised things had to change. Ustinov had put warts all over his face and when he came to kiss her in the second act, one of them stuck to her chin. She corpsed completely ('corpsing' is actor speak for collapsing into giggles). Ustinov, as you might imagine, was stern. So what next for her? 'I started having babies, actually.' She met Bourne on a blind date. 'Lily was on the way before I could click my fingers.' (Lily is now 17; they also have a son, Ben, 15.)

|

| Old Vic director Kevin Spacey and Elton John, who wrote the songs for Billy Elliot. |

Is Bourne an enabler or a set of brakes? 'Both, but I need a set of brakes because I'm off the brake!' Then she adds: 'He's a tax exile now, you know. He lives in Monte Carlo.' Does she visit at weekends? 'Sometimes. Yes. That's where he lives. In Monte Carlo.' (This is paradoxical: Bourne once donated money to the Labour party. He also, for the record, tried to buy the dome at roughly the same time as he and his wife threw a birthday party for Peter Mandelson, which didn't play particularly well in the media.)

It was her father who first suggested that she look at the Richmond Theatre, which, at the time, was falling to pieces, as a project to keep herself busy. She would sit in a Portakabin, heavily pregnant, trying to raise money (they spent £5.2 million on it in the end, though it is now part of the Ambassadors Group). Her father, however, died just weeks after she and Robert took it on and, not too long afterwards, she lost her sister, Georgina, to breast cancer; she was in her early thirties and left a young son.

This must have been a terrible time. 'Yes, but in a way that is what makes me go forward. I look at Georgina... she had so little time to make an impact on the world. I'd like to make my mark. I'll tell you, the death thing is not as shocking as watching someone you love go through pain. She was unrecognisable to me when she died. She looked like a skull. I fainted. It was just me and her husband and family in the room. I had to have a brandy. I'd never had a brandy before in my life. I was so shocked by it. It pulls you back a bit, but not for long. You think, "I'm going to do it for them.'"

Greene didn't know anyone when she started; now, of course, she knows everyone (though she has always impressed a certain kind of alpha-male: at 19, she was offered a holiday job as part of Frank Sinatra's entourage on his European tour. Ol' Blue Eyes took a shine to her and she ended up in his hotel room. 'He went to the bathroom,' she once said, 'and when he walked out, he was wearing braces on his socks. I thought it was very funny. He didn't.' Even so, he still gave her a gold key ring inscribed: 'To Sally. With love and peace. Frank Sinatra.')

Is she out every single night, hanging with Elton and Stephen and Peter and the rest? 'You have to a bit because you're selling entertainment. But I pick and choose. I don't really like champagne.' In any case, the biggest address book in the world doesn't necessarily help when it comes to raising hard cash. 'I've taken a couple of mortgages out in my life, I have to say. Fund raising is getting harder and harder. People have so many commitments.'

GREENE SAYS that the simple fact of it is this: some shows make money and some don't, and it 'sort of evens out in the end'. The first play she ever put on - it was a singlehander starring Nicol Williamson, who famously stormed off stage and urged the audience to follow him - had a budget of about £200,000, but Billy Elliot is costing many millions (she avoids saying precisely how many). 'What you hope for is something like Billy Elliot, which is a huge risk, but should give a big return.'

Her current fantasy is to persuade George Clooney to do a comedy here; he didn't like the first play she sent him, but he wants to keep talking. Isn't she wary of this trend for stars on stage? Doesn't it distort the shape of the West End (quite apart from the fact that, in the last analysis, some of them can't really cut it)? She sounds rather tart. 'I think you'll find Olivier ran the National Theatre with stars. It's not a new thing. And if they can do the job... Kevin is a fantastic actor.'

Which brings me, neatly, back to Mr Spacey. By now, we have been joined at the lunch table by Nick, Greene's assistant, who has brought with him a piece of paper entitled: 'Nicola's notes' (I think Nicola is in charge of press at the Old Vic; Nick is having the lamb). The piece of paper lists seven numbered points. These address some of the issues Greene will not discuss with me. 'The first Old Vic Theatre Company season is going well,' instructs point number one. 'Kevin is enjoying himself on stage and is busy planning next season,' says point five. And point six? 'Critics are a fact of life.' Good grief. Who wrote this stuff?

I admire Sally Greene hugely. Only a churl would knock her enthusiasm or her achievements. In person, she is charming: warm and good at names. But I do wish that, in conversation, she had the courage of her convictions. After all, who could blame her if, every once in a while, she felt like emitting a blood-curdling, theatrical scream? Not me, that's for sure.

![]()

RETURN | RÉSUMÉ (ENGLISH) | RÉSUMÉ (RUSSIAN) | HOME

![]()